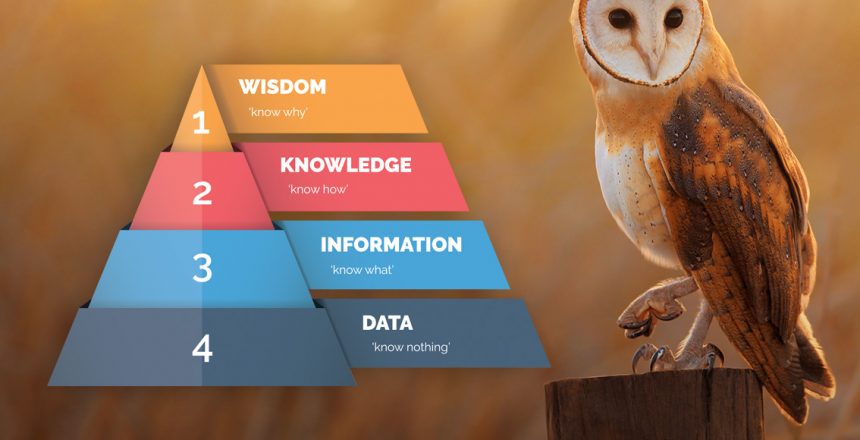

Data has been described as ‘know nothing’. To be useful, it needs to be converted into Information (know ‘what’), then Knowledge (know ‘how’) and finally Wisdom (know ‘why’).

The origin of the Data-Information-Knowledge-Wisdom (DIKW) framework (see Figure above) is unknown, but likely dates to a 1934 play by TS Eliot: ‘Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge? Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?’

A lot of data is required to create a little wisdom – analogous to refining large quantities of maple sap into a single serving of maple syrup. According to Albert Einstein ‘wisdom is not a product of schooling but of the lifelong attempt to acquire it.’ An alternative definition is that information and knowledge inform our decisions about ‘doing things right’, while wisdom helps us to do the right thing.

Between each component of the DIKW pyramid is a conversion zone where the components are transformed into other types of intelligence. Conversion can be automated or manual and are performed by humans or software.

If a component expands quicker than the rate at which it can be converted, a bottleneck forms in its conversion zone, and the pyramid becomes a funnel. Resources are re-allocated from the other conversion zones to help manage the overload of data, thereby reducing the rate at which knowledge and wisdom are created. Big Data can therefore paradoxically cause knowledge decay and decrease wisdom.

Unfortunately, Big Data and bottlenecks are often exploited for nefarious purposes. ‘Quote stuffing’ is the practice of intentionally flooding financial markets with bogus data. Spikes in data create temporary bottlenecks in systems when the capacity of systems to convert data into information and knowledge is exceeded. Criminals have been manufacturing and exploiting these bottlenecks for years. In 2010, Quote Stuffing memorably wiped 140 billion dollars from financial markets in a single day! ‘Fake news’ works in a similar way by intentionally flooding social media with false data.

Franklin Foer argues in his book ‘World without mind: the existential threat of big tech’ that social media and search engines have: ‘presided over the collapse of the economic value of knowledge which has severely weakened newspapers, magazines and book publishers. By collapsing the value of knowledge, they have diminished the quality of it’.

The specialty of general practice has been experiencing its own explosion in Big Data. While Big Data will undoubtedly be helpful, we should remain mindful of just how much time and effort are required to convert data into knowledge and wisdom.

We should also appreciate that the knowledge or wisdom of one person enters the DIKW hierarchy of others as data or information that requires assimilation and conversion before it becomes their knowledge and wisdom.

The feeling of ‘drowning in data’ is becoming all too familiar in our modern society. While it may not be completely avoidable, it is useful to consider whether our ability to generate and use knowledge and wisdom are being (intentionally) compromised. Sometimes less is more.